1969 was a year of protests. In the spring, a group of largely African American students led by SOULS (Society of United Liberal Students) presented a list of demands to President Leo W. Jenkins for immediate action to correct racial problems at ECU. Before the semester was over, displays of Confederate flags and performances of “Dixie” were banned on campus. In the fall, student activism took a new direction: organized opposition to the Vietnam War. Outspoken resistance to the draft coupled with vocal advocacy of withdrawal from Vietnam, the suffrage for 18-year old’s, and full recognition of student rights made the fall of 1969 one of the most politically charged semesters in East Carolina’s history. While the fall protests were successfully staged without major incident, their outcomes were by comparison with those of the spring, of a different variety.

1969 was also the first year of Richard M. Nixon’s (1913-94) presidency. Nixon had campaigned against continued involvement in the war but emphasized the importance of empowering South Vietnam to fight Communist North Vietnam as a prelude to American withdrawal. Following his inauguration in January 1969, however, Nixon escalated the war, resulting in nearly 12,000 Americans killed during his first year in office. In the meantime, the draft continued to call young men into service, making the war especially unpopular on college campuses. When news of the 1968 Mai Lai massacre was revealed to the American public in November 1969, anti-war sentiments reached unprecedented heights.

Even before news of the Mai Lai massacre broke, a Vietnam Moratorium Committee had declared October 15 a day of national protests meant to accelerate the end of the war. One strategy emphasized was to make “Moratorium Day” as peaceful, law-abiding, and mainstream as possible so as to avoid its offhand dismissal as something for hippies and the radical counterculture. Local expressions of the Moratorium movement recruited clergy, professors, college students, community leaders, as well as leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. The first Moratorium Day, held on Wednesday, October 15, succeeded impressively with millions participating worldwide in an overwhelmingly peaceful display of popular, educated opposition to the war. The success of the first moratorium day led to a second scheduled a month later, on November 15, nationwide in scope but centered in Washington, D.C., in and around the mall, circling the White House and bringing the message front and center to President Nixon. The D.C. event alone attracted nearly a million people while nationwide, millions more reportedly participated. Again, the second Moratorium Day was staged largely without violence or conflict.

At ECU, a new student group, GAP (referring to the generation gap, and the chasmic divide of social and political consciousness resulting from it), emerged, spearheading student participation in marches, protests, and political initiatives centered around opposition to the Vietnam War, but also concerned with student rights, ongoing racial tensions in the community, and local government efforts to prevent anti-war protest strategies. Early on, Whitney “Whit” Hadden chaired GAP and helped in coordinating its efforts. Hadden was, incidentally, the son of Rev. William James “Bill” Hadden, Jr. (1921-1995), Episcopal chaplain at ECU who was active in the community in fighting segregation through his leadership position as the first chair of the Good Neighbor Council and later work on the Greenville City Council. Rev. Hadden offered the opening invocation at the ECU event and his son spoke on the importance of peace.

As part of its October 15 activities, the ECU Vietnam Moratorium Committee – which included a significant contingent of GAP members – featured a “teach-in” from 9:00-4:30 staged on the mall, with prayers by local clergy opening each hour. President Leo Jenkins and Professors William White (History), Philip Adler (History), Tim Britton (Sociology), and Sydney Finkel (Business) each delivered remarks. In his address which was later published in the Fountainhead, Jenkins stated, “Most thinking Americans realize that the Vietnam war is unfortunate for all concerned. We don’t relish or enjoy any programs that bring about a loss of our human or physical resources. We can however express our desire for the conclusion of this conflict without missing classes.” Following the teach-in, moratorium participants went into residential areas ringing doorbells in an attempt to awaken the community to the need to end the war.

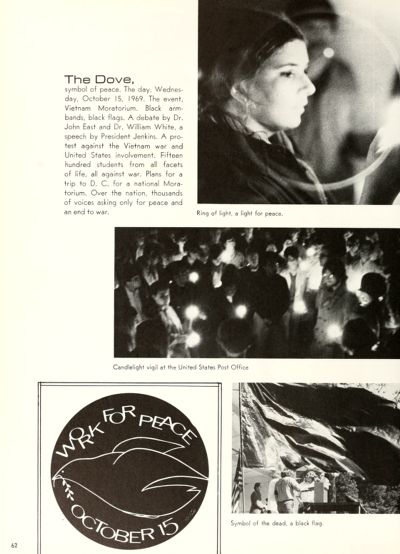

ECU was not alone: Davidson College, Wake Forest, Belmont Abbey College, UNC-CH, NC State, Shaw University, UNC-C, Queens College, Guilford College, UNC-G, A&T University, Johnson C. Smith University, Appalachian State University, Elon College, High Point University, Fayetteville State University, Pfeiffer College, Western Carolina University, and Catawba College also participated. The ECU Teach-in drew approximately 1,500 students, faculty, staff, and community members. In addition, some 1,800 attended a debate between Professors John East (Political Science), pro, and William White (History), con, over the Vietnam War. A candlelight vigil – held at the new Post Office on Second Street – concluded the day. Organizers had hoped to have the vigil on the town commons, but Greenville city officials declined to issue a permit. Cognizant of the movement’s power, President Nixon, in an attempt to coopt its appeal, declared October 22 a National Day of Prayer for realization of peace and justice.

Building on the successes of October 15, the ECU Moratorium Committee, often meeting at the Baptist Student Union, organized ECU’s contribution to the second round of the national movement, a local march staged on November 13. The ECU Moratorium Committee also provided 27 participants for the Washington, D.C. “March Against Death” on November 15 on the mall. Participants carried placards bearing the names of American soldiers killed in Vietnam. The ECU contingent left immediately following the Nov. 13 Greenville march, with lodging and transportation provided. The D.C. march, conducted in silence and without incident, was led by Mrs. Coretta Scott King, Rev. William Sloan Coffin, and Dr. Benjamin Spock. Amplifying the impact of the D.C. march was, as earlier, TV coverage, in color, by each of the national networks – CBS, NBS, and ABC – bringing the anti-war protest movement into American homes nationwide.

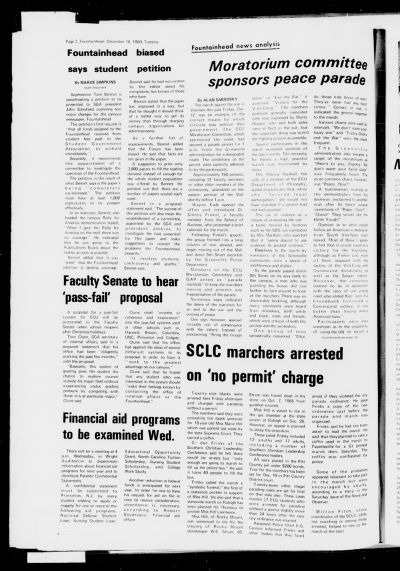

On December 12, yet another peace march was conducted down Fifth Street, including 150 participants led by the ECU Moratorium Committee. Despite earlier criticism of a city ordinance requiring permits for parades and marches, the Moratorium Committee secured a permit and complied with all city regulations. Members of GAP and the Moratorium Committee served as “marshals” ensuring that the march met every dimension of the law. The same afternoon, however, 29 African Americans – some of whom had participated earlier in the anti-war march that day — were arrested as they marched without permit in protest against the decision by the N.C. Supreme Court to uphold the death sentence for Marie Hill, an 18-year-old from Rocky Mount convicted of murdering a storekeeper. Golden Frinks, field secretary of the local Southern Christian Leadership Conference and on-the-scene leader of the impromptu march, was informed of the ordinance by the authorities in advance, but the march proceeded regardless.

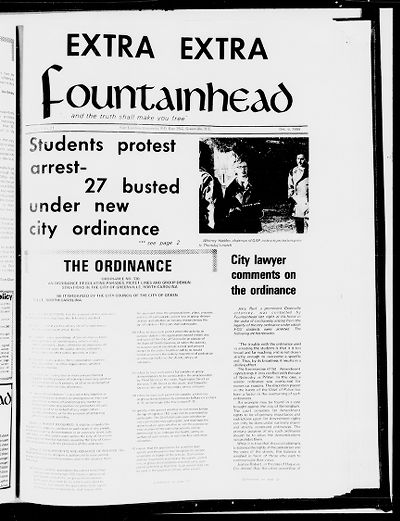

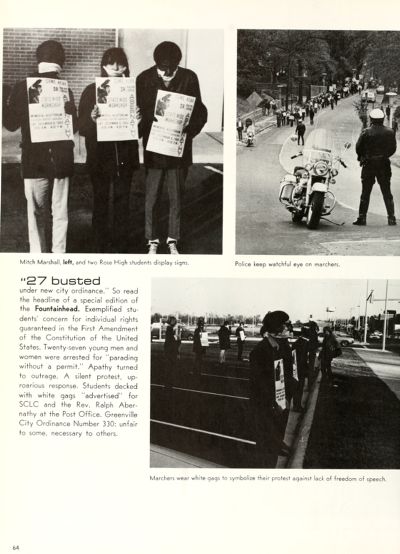

The 29 arrested added to the total number arrested in December: 27 ECU students had been arrested on December 4, just over 24 hours after the controversial ordinance went into effect. The ECU students were in turn protesting the earlier arrest of two black female members of the SCLC – Daisy L. Albritton, 22, and Margaret M. Marshall, 22, both former ECU students — for illegally posting posters on telephone poles advertising the arrival of Ralph Abernathy, head of the SCLC, in Raleigh to mediate a strike at UNC-CH. The ECU demonstrators had marched silently from campus to Evans Street, their mouths covered in gag-fashion with cloth or tape and were thereupon arrested by Greenville police. Another group of demonstrators, also with their mouths covered and carrying posters about Abernathy’s visit, gathered at the new Second Street Post Office, but were not arrested.

As the fall protests veered into breaches of the law and mass arrests, some of the momentum for the anti-war movement dissipated. Fall semester exams and then the beginning of the holiday break no doubt also contributed to a new climate on campus and in Greenville. The 1970 spring semester occasioned few reverberations of the anti-war movement as activist energies were redirected towards environmental issues with the new year becoming one of heightened ecological consciousness. Even GAP and its somewhat radical coterie shifted its attention to the environment. Elsewhere in the nation, however, anti-war activity remained pronounced, culminating in the tragic Kent State massacre in the late spring of 1970, and promptly reviving at ECU another round of activism in opposition to the war.

Sources

- “200 + observe protest.” Fountainhead. December 16, 1969. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39448

- “27 Arrested in Greenville.” News and Observer. December 5, 1969. P. 10.

- “27 busted under new city ordinance.” Buccaneer. 1970. P. 64. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15321

- “Abernathy Poster Violates Law; 2 Charged.” Charlotte Observer. December 5, 1969. P. 6.

- “Action reflects concern over ecology, National Teach-In planned for April 22.” Fountainhead. March 19, 1970. Pp. 8-9. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39464

- “Anti-war programs staged Wednesday.” Fountainhead. October 14, 1969. Pp. 2, 5. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39434

- “Arrests Follow SCLC Protest.” Charlotte Observer. December 13, 1969. P. 12.

- “City lawyer comments on ordinance.” Fountainhead. December 6, 1969. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39445

- “Delta Sigma Phi.” Buccaneer. P. 240. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15320

- “Earth Day observance set.” Fountainhead. April 20, 1970. P. 1, 6-7. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39469

- “Earth Day attendance was sad disappointment.” Fountainhead. April 23, 1970. P. 8. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39470

- “Former students arrested for putting up posters.” Fountainhead. December 4, 1969. P. 3. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39444

- “GAP members mount drive to clean up on Earth Day.” Fountainhead. April 23, 1969. P. 1, 3. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39470

- “Jenkins comments on war – looks for way out.” Fountainhead. October 23, 1969. Pp. 8-9. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39437

- “Local ACLU elects board of directors.” Fountainhead. November 6, 1969. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39441

- “Local Earth Day activities will be observed on April 22 with workshops and discussions.” Fountainhead. April 13, 1970. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39467

- McDowell, Robert. “Anti-war festival set for Chapel Hill.” Fountainhead. April 9, 1970. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39466

- McDowell, Robert. “Anti-war festival draws thousands.” Fountainhead. April 16, 1970. P. 5. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39468

- McDowell, Robert. “Cumulative effects of pollution unknown.” Fountainhead. April 27, 1970. P. 11. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39471

- “Moratorium.” Fountainhead. October 23, 1969. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39437#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=1&xywh=1803%2C3602%2C943%2C969

- “Moratorium group plans statewide march on city.” Fountainhead. December 9, 1969. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39446

- “Moratorium support continues to grow.” Fountainhead. October 9, 1969. P. 12. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39433

- “October 15.” Fountainhead. October 2, 1969. P. 15. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39431

- “Ordinance is unjust.” Fountainhead. December 9, 1969. P. 12. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39446

- “Protests do not exclude patriots.” Fountainhead. October 23, 1969. P. 11. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39437

- “Racial incidents Friday close Rose High School.” Fountainhead. October 28, 1969. Pp. 1-2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39438

- “Rose High School plans to open today, Board of Education meets on problems.” Fountainhead. October 30, 1969. Pp. 3-4. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39439

- “SCLC marchers arrested on ‘no permit’ charge.” Fountainhead. December 16, 1969. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39448

- “Students ask strike for academic freedom.” Fountainhead. December 6, 1969. P. 3. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39445

- “Students ask strike for academic freedom.” Fountainhead. December 11, 1969. P. 3. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39445

- “Students protest arrest – 27 bused under new city ordinance.” Fountainhead. December 6, 1969. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39445

- “Students protest Greenville ordinance.” University Archives # 50.01.1970.64 . J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, N. C. http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/11012

- “The Dove.” Buccaneer. 1970. P. 62. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/15321

- “The Nation’s campuses prepare for moratorium.” Fountainhead. October 14, 1969. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39434

- “’The Revolution is coming.’” Fountainhead. April 16, 1970. P. 6. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39468

- “UNC-CH completes plans for Vietnam moratorium.” Fountainhead. October 7, 1969. P. 3. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39432

- “Vietnam Moratorium.” Fountainhead. October 14, 1969. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39434

- “Vietnam Moratorium marks full day of activities.” Fountainhead. October 16, 1969. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39435#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-164%2C679%2C4869%2C5000

- Blansfield, Karen. “Political Science professor takes poll on attitudes toward demonstrations.” Fountainhead. October 30, 1969. P. 6. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39439

- Blansfield, Karen. “Memorial Demonstration held for slain Kent State students.” Fountainhead. May 7, 1970. P. 1. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39474

- Connelly, Bill. “Doubt surrounds march.” Fountainhead. November 6, 1969. P. 10. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39441

- Eads, Wayne. “Does the draft overrule conscience?” Fountainhead. October 2, 1969. Pp. 8-9. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39431

- Fair, Donna. “Abernethy addresses rally in Raleigh Saturday.” Fountainhead. December 9, 1969. P. 4. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39446

- Griffin, Charles. “Radicals test ordinance.” Fountainhead. December 16, 1969. P. 6. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39448

- Hadden, Whitney. “Larry Little, N.C. Black Panther talks of changes.” Fountainhead. June 23, 1971. Pp. 3, 5. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39565

- Hardee, Roy. “29 Marie Hill Protesters Are Arrested in Greenville.” News and Observer. December 13, 1969. P. 3.

- Hord, James. “Antiwar drive swells in U.S.” Fountainhead. October 7, 1969. P. 19. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39432

- McDowell, Robert. “Give Peace a Chance, October 15.” Fountainhead. October 8, 1969. Pp. 6-7. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39433

- Nelson, Eldon. “Concerned persons unite efforts for Earth Day.” Fountainhead. April 20, 1970. Pp. 6-7. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39469

- Robinson, Bob. “Students review war.” Fountainhead. October 16, 1969. Pp. 6-7. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39435

- Sabrosky, Alan. “Conservative commentary.” Fountainhead. December 9, 1969. P. 12. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39446

- Sabrosky, Alan. “Moratorium committee sponsors peace parade.” Fountainhead. December 16, 1969. Pp. 2-3. http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39448

- Sievert, Bill. “Lower voting age.” Fountainhead. November 4, 1969. P. 8. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39440

- Waynick, Capus M. 1964. North Carolina and the Negro (Raleigh: North Carolina Mayors' Co-operating Committee, 1964), Pp. 93-101.

- William J. Hadden Oral History Interview. Donald Lennon, interviewer. June 13, 1905?. Oral History #OH0259. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/special/ead/findingaids/OH0259/

- Wendelin, David. “’March Against Death’ proceeds.” Fountainhead. October 9, 1969. P. 9. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39439

- Wendelin, David. “March permit requested.” Fountainhead. November 6, 1969. P. 2. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/39441

- William J. Hadden Oral History Interview (#OH0259). East Carolina Manuscript Collection. J. Y. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, North Carolina. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/special/ead/findingaids/OH0259/

Additional Related Material

The Vietnam Moratorium Committee of ECU advertises the October 15 day of hope and peace for Vietnam. Image Source: Fountainhead. October 2, 1969.

"Students protest arrest-27 busted under new city ordinance." Image Source: Fountainhead. December 6, 1969.

"200+ observe protest." Image Source: Fountainhead. December 16, 1969

Image Source: The Buccaneer, 1970

Image Source: The Buccaneer, 1970

Citation Information

Title: Anti-War Protests, 1969

Author: John A. Tucker, PhD

Date of Publication: 10/14/2020